“We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”

– T. S. Eliot

If viewing an exotic and very different culture can help us leap out of the water of our own culture to truly see it, the Nacirema need to be high on our list of cultures to examine. In 1956, cultural anthropologist Horace Miner’s original article (Links to an external site.) about the Nacirema provided an in-depth look at their ritual behaviors that show, in Miner’s words, “the extremes to which human behavior can go.” The work was so shocking and revealing that the article went on to be the most widely read article in the history of Anthropology.

As Miner explains in the article, the Nacirema are obsessed with the body, which they believe is intrinsically ugly and prone to debility and disease. Each Nacirema household has a shrine or sometimes several shrines in which private rituals are performed to mitigate what they see as ever-present and pervasive threats to their bodies. Various charms provided by medicine men are ingested, and they perform several rites of ablution throughout the day using a special purified water secured from the main Water Temple of the community.

Since Miner’s time, the Nacirema have started building very large temples called “mygs” that contain rows and rows of various body torture devices which they use to punish their own bodies. The devices are designed to tear and damage muscles, causing them to swell. Others are designed to completely exhaust the body and use up all of its energy so that the body starts to consume itself in order to provide energy for movement.

While the Nacirema believe that these rituals make their bodies stronger and more resilient to disease, the primary purpose of these rituals seems to be to transform the shape of the body to conform to Nacirema ideals. These ideals are so extreme that they are beyond the reach of natural human capacity. To achieve these ideals, some Nacirema go so far as to have ritual specialists cut them open and inject liquids into areas of their body that they desire to be larger, or remove soft body tissues and make other parts of their body smaller.

These new temples are just one example of how cultures are always changing, and over the past 70 years, the Nacirema have changed dramatically. For the Nacirema of Miner’s study in 1956, even simple black-and-white televisions were a new and exotic technology. Today the Nacirema can be found across the social media landscape on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and YouTube. This offers us the ability to observe this exotic culture simply by tuning in to their YouTube channels.

One of the more interesting rituals of the Nacirema is the strecnoc. Hundreds and sometimes thousands of people attend these rituals which take place around a large, elevated ritual platform known as an egats. The rituals are often at night, so the egats is lit up in spectacular fashion. Attendees gather in the dark around the egats and often consume mind-altering substances such as lohocla and anaujiram while they wait for the ritual leader to arrive. Attendees are often shaking with anticipation as they wait for the ritual to begin, and the first sighting of the ritual leader on the egats can send attendees into a frenzy of excitement, jumping up and down, screaming, with arms high in the air as if struggling to reach out and touch the ritual leader and feel their power.

In the late summer of 2013, I decided to examine one of these rituals in more detail. I did a YouTube search and watched the most-watched strecnoc of recent days. A large effigy of a bear, one of the most dangerous and feared animals among the Nacirema, was placed at the center of the egats. The bear was approximately 30 feet tall and styled to look like the small toy bears of Nacirema children.

Nacirema children, who are often required by their parents to sleep alone (a rare practice across cultures around the world), often sleep with these small toy bears, seeing them as protectors and often building up strong imaginary friendships with them.

Suddenly, a door opened up in the stomach of the large bear and the ritual leader stepped out from inside. Dancers in toy bear costumes rushed in from the sides of the egats to join her. Together they took to the center of the egats and started doing a special dance that is normally only performed in the privacy of one’s own room. It is an especially wild dance, not really meant for anyone to see, in which you simply allow your body to do whatever it feels like doing. This often results in a steady but awkward thrusting or shaking motion while the arms spontaneously mimic whatever is heard in the music. If a handheld string instrument is being played, the arms might move as if to hold it (ria ratiug). If drums are being played, the arms move as if to play the drums (ria smurd), and so on. It is a very fun form of dance to do, but it is usually not meant to be seen, and some attendees were uncomfortable watching it, especially as the ritual leader moved more deeply into this private dance and let her entire body move freely but awkwardly. Even her tongue seemed to be out of control, flailing wildly about her face.

It’s our party we can do what we want.

It’s our party we can say what we want.

It’s our party we can love who we want

We can kiss who we want

We can see who we want

As the voice continued to poetically espouse these core Nacirema ideals of freedom and free choice, the ritual leader continued to demonstrate these values with her body. She bent over and started shaking her backside in an attempt to isolate a contraction of her gluteus maximus muscles which then send the fatty area of the buttocks region into a wave-like motion known as gnikrewt. This is often interpreted as being very sexually suggestive, and the mixture of childhood toys along with such sexually suggestive dancing (tongue flailing about, buttocks shaking), was simply too much for some of the attendees.

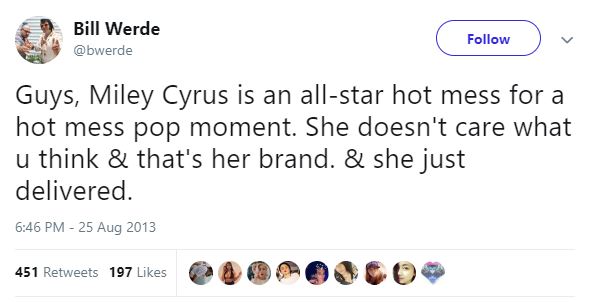

Ultimately, the Nacirema were deeply divided on the quality of the performance. It seemed as if there was no middle ground. You either hated it, or you loved it.

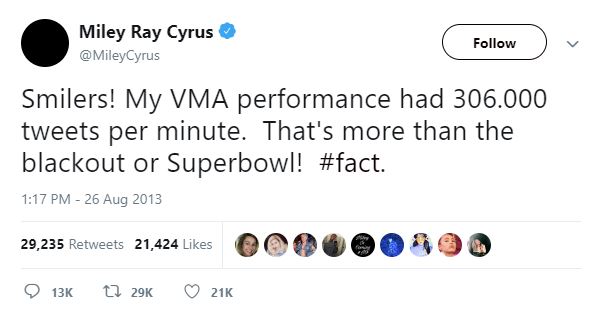

Even as the media criticized her performance, with many saying that it was likely the end of her career, the ritual leader, Yelim, turned their words to her advantage and celebrated the event as a great success.

As an anthropologist, I thought it was one of the most significant artistic performances I had ever seen, a telling portrait of what it is like to grow up among the Nacirema. The toy bears, the awkward “dance like nobody’s watching” dancing that you do in your room as a young child, and the ritual dress that included a cartoon mouse on a little girl’s tutu were clear marks of childhood, all of which were shed throughout the performance. The bears transformed into full- bodied voluptuous women. The little girl’s tutu was shed to reveal a flesh-toned bikini, and the awkward and childish dancing transformed into a sexual feast of humping, grinding, and gnikrewt. She was shedding the skin of her childhood, initiating herself into her own adulthood right in front of our eyes, struggling to show the world that she is now a full adult, not that little girl Aannah Anatnom.

Those Nacirema who had to turn away and just couldn’t stand to watch it were probably seeing a little too much of their own awkward childhood and transition to adulthood, for the Nacirema transition to adulthood is always awkward. It is, as they say, a “hot mess.”

The cost of their core values of freedom and choice is that there are no limitations or guidelines on how to grow up properly. There are no clearly defined rules for what it means to be an adult. There are no clearly defined pathways for becoming independent. Instead, there are options at every turn of life. The Nacirema cherish these options. But they also make growing up very, very hard.

Children are raised with the idea that they can “be whatever they want to be.” They are taught to question and distrust any message that attempts to tell them who they are or how they should behave. “Be true to yourself,” is a commonly espoused Nacirema proverb. Yelim echoed these sentiments in her performance, “We don’t take nothing from nobody.” But because they “don’t take nothing from nobody,” like advice or values, they are left with nothing to guide them. They set off on a lifelong quest to figure out what they want to do and who they want to be. “Who am I?” is a question that dominates the Nacirema psyche.

As a result, many Nacirema make it their life goal to “find” their “self.” Though most Nacirema take this goal for granted, it has not always been this way. Even in Miner’s time, the 1950s, things were different. Back then people were often encouraged to conform and follow the rules of society. But by the late 1970s, books like William Glasser’s “The Identity Society” and Christopher Lasch’s “Culture of Narcissism” documented a shift from a culture that valued humility and “finding one’s place” to one that valued self-expression and “finding one’s self.”

THE POWER OF CONTINGENCY AND “MAKING THINGS FRAGILE”

It is obvious at this point that the Nacirema are not some exotic culture, but are in fact American, and that “Nacirema” is just “American” spelled backwards. This was Miner’s trick. He forced us to see the strange in the familiar and used the art of seeing like an anthropologist on his own culture.

This trick is one method of “seeing your own seeing” without going to an exotic culture. You can find the exotic right around you, and the more mundane, the better. Because when you reveal that even the most mundane beliefs and practices that make up your life can be viewed as strange and exotic, they also become contingent, which is a fancy way of saying that they need not exist or that they could have been different. Our beliefs and practices are contingent upon the historical and cultural conditions that led to them. And once we recognize them as contingent, we can ask new questions about them.

What is a self? Is it really a thing? Or is it something you do? Would it be better to say that we “create” ourselves rather than “find” it? And what did that other great poet, Marshall Mathers, mean when he said “You gotta lose yourself”? Is it possible that you have to lose your self in order to find your self? If so, what is this “self” that must be lost? Am “I” the same thing as my “self”? If they are the same, how can I say “I” need to find my “self”? Can “I” really find, lose, or create my “self” or do I just need to let the “I” be my “self”?

These are a special kind of questions. These questions do not require answers; the questions are insights in themselves. They give you new alternatives for how to think about your life. They give you a little bit of freedom from the limited perspectives offered by your taken-for-granted assumptions, ideas, and ideals.

Michel Foucault, a social theorist and historian who has had a large impact on anthropology, says that this kind of analysis is a way of “making things more fragile.” It shows that “what appears obvious is not at all so obvious.” In his work, Foucault he tries to show that many of the “obvious” facts of our lives that we take for granted can be “made fragile” through cultural and historical analysis. In this way, we “give them back the mobility they had and that they should always have.” The ideas and ideals of our culture do not have to have total power over us. We can play with them, make them more fragile, and thereby take some of that power back.

This particular power of the anthropological perspective has been at the heart of anthropology since its founding in the late 1800s. Franz Boas, the father of American Anthropology, said that his whole outlook on life had been determined by one question:

How can we recognize the shackles that tradition has laid upon us?

For when we recognize them, we are also able to break them.

LEARN MORE