All cultures are dynamic and constantly changing as individuals navigate and negotiate the beliefs, values, ideas, ideals, norms, and meaning systems that make up the cultural environment in which they live. The dynamics between liberals and conservatives that constantly shape and re-shape American politics is just one example. Our realities are ultimately shaped not only in the realm of politics and policy-making, but in the most mundane moments of everyday life.

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz famously noted, echoing Max Weber, that “Man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun.”

These webs of significance create a vast network of associations that create the system that brings meaning to the most minute moments of our lives and dramatically shape the decisions we make. Due to these “webs of significance,” even the simple decision of which coffee to drink can feel like a political decision or some deep representation of who we are as a person.

In a recent BuzzFeed video, a woman sits down for a blind taste test of popular coffees from Dunkin’ Donuts, Starbucks, McDonalds, and 7-11. As she sits, the young woman confidently announces her love for Dunkin Donuts coffee. “Dunkin’ is my jam!” she says, declaring not only her love for the coffee but also expressing her carefree and expressive identity. But as she takes her first sip from the unmarked cup of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee she nearly spits it out and screams, “This is the worst!” and then confidently proclaims that that cup had to be “7-11!” She eventually settles on the 4th cup from the left as the best. When she is told that she has chosen Starbucks, it seems to create a minor identity crisis. She covers her head in shame, “Oh my god, I’m so against big business.” Her friend, who has also chosen Starbucks, looks to the sky as if having a revelation about who he is. “We’re basic,” he says. “We’re basic,” she repeats, lowering her head in shame and crying with just enough laugh to let us know that she is kidding, but only kind of kidding.

Another woman, elegantly dressed in a black dress with a matching black pullover and a bold pendant, picks McDonald’s – obviously well “below” her sophisticated tastes. She throws her head back in anguish and then buries her head in her hands as she cries hysterically, but a little too hysterically for us to take it too seriously. She wants us to know that this violates her basic sense of who she is, but that she is also the type of person who can laugh at herself.

The point is that what tastes good to us – our taste for coffee, food, music, fashion, or whatever else – is not just a simple biological reaction. There is some of that, of course. We are not faking it when we enjoy a certain type of music or drink a certain type of coffee. The joy is real. But this joy itself is shaped by social and cultural factors. What tastes good to us or strikes us as beautiful or “cool” is shaped by what it means to us and what it might say about us.

What tastes good to us or strikes us as beautiful or “cool” is shaped by what it means to us and what it might say about us.

The simple “high school” version of this is to say that we are all trying to be cool, and though we may try to deny it as we get older, we never stop playing the game. We are constantly trying to (1) shape our taste to be cool, or (2) shaping “cool” to suit our taste. Replace the word “cool” with “culture” and you see that we have one of the fundamental drivers of cultural change. We shape our taste (which could include our taste in food, politics, rules, roles, beliefs, ideals) to be acceptable, while also attempting to shape what is acceptable (culture) to suit our tastes.

Over the past twenty years American “hipsters” have been attempting to create and re-create what counts as “cool” in American culture by piecing together the old and new, the masculine and the feminine, in ever-changing ways.

Over the past twenty years American “hipsters” have been attempting to create and re-create what counts as “cool” in American culture by piecing together the old and new, the masculine and the feminine, in ever-changing ways.

Why Something Means What it Means

In 2008, Canadian satirist Christian Lander took aim at the emerging cultural movement of “urban hipsters” with a blog he called “Stuff White People Like.” The hipster was an emerging archetype of “cool” and Landers had a keen eye for outlining its form, and poking fun at it. The blog quickly raced to over 40 million views and was quickly followed by two bestselling books.

In post #130 he notes the hipster’s affection for Ray-Ban Wayfarer sunglasses. “These sunglasses are so popular now that you cannot swing a canvas bag at a farmer’s market without hitting a pair,” Lander quips. He jokes that at outdoor gatherings you can count the number of Wayfarers “so you can determine exactly how white the event is.” If you don’t see any Wayfarers, “you are either at a Country music concert or you are indoors.”

Here Landers demonstrates a core insight about our webs of significance and why something means what it means. Things gather some of their meaning by their affiliation with some things as well as their distance from other things. In this example, Wayfarers are affiliated with canvas bags and farmers markets, but not Country music concerts. The meaning of Wayfarers is influenced by both affiliation and distance. They may not be seen at Country music concerts, but part of their meaning and significance depends on this fact. If Country music fans suddenly took a strong liking to Wayfarers, urban hipsters might find themselves disliking them, as they might sense that the Wayfarers are now “sending the wrong message” through these associations with Country music.

Quick Quiz: Which of these bumper stickers would you expect to find on a Toyota Prius or Subaru Outback but not a Hummer or large pickup truck?

Can you match the stickers and music with the vehicle? Of course you can. Symbols hang together. They mean what they mean based on their similarity and differences, their affiliations and oppositions. So the meaning of OneBigAssMistakeAmerica gains some of its meaning from being affiliated with a truck and not with a Prius. The cultural value of the truck and Prius depend on their opposition to one another. They may be in very different regions of the giant web of culture, but they are in the same web. It isn’t that there are no Indie music fans who hate Trump and drive trucks. Some of them do. But they know, and you know, that they are exceptions to the pattern.

The meaning of symbols is not a matter of personal opinion. Meanings are not subjective. But they are not objective either. You cannot point to a meaning out in the world. Instead, cultural meanings are intersubjective. They are shared understandings. We may not like the same music or the same bumper stickers, but the meanings of these things are intersubjective, or in other words, I know that you know that I know what they mean.

At some level there is broad agreement of meanings across a culture. This facilitates basic conversation. If I gesture with my hands in a certain way, I can usually reasonably assume that you know that I know that you know what I mean. But the web of culture is also constantly being challenged and changed through the complex dynamics of everyday life. The web of culture does not definitively dictate the meaning of something, nor does it stand still. We are all constantly playing with the web as we seek our own meaningful life.

We use meanings and tastes as strategic tools to better our position in society and build a meaningful life, but as we do so, we unwillingly perpetuate and reproduce the social structure with all of its social divisions, racial divides, haves and have-nots. This is the generative core of culture. In Lesson Six, we explored the idea that “we make the world.” In this lesson we start digging into the mystery of how we make the world.

TASTE AND DISTINCTION

Why do you like some music and hate others? Why do you like that certain brand of coffee, that soft drink, those shoes, clothes, that particular car? In a famous study published in 1979, French anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu put forth the idea that our tastes are strategic tools we use to set ourselves apart from some while affiliating with others. Taste is the pursuit of “distinction,” the title of his book.

Bourdieu needed to invent new concepts to explain how taste and distinction work within a society. He pointed out that tastes have cultural value. The right taste can be an important asset as you make your way through society and try to climb the social ladder. So he invented the notion of “cultural capital” to refer to your cultural knowledge (what you know), “social capital” to refer to your social network (who you know) and pointed out (importantly) that what you know and who you know play a strong role over the course of a lifetime in how much you own (economic capital) and your social status.

Cultural Capital + Social Capital => Economic Capital

Cultural capital includes your ability to catch the passing reference to books, movies, and music of the cultural set you aspire to be a part of during a conversation. It includes your capacity to talk with the right words in the right accent about the right things. It includes your ability to dress right, act right, and move right. And it includes your taste, an ability to enjoy the right music, foods, drinks, movies, books, and fashion, among other things.

What is “right” for one person is not necessarily “right” for another. If you aspire to be an affluent urban intellectual hipster, the cultural capital you will set about accumulating is very different from the cultural capital sought after by someone pursuing acceptance as authentically Country. Importantly, this distinction between the two sets is essential to the vitality of each. As Carl Wilson explains, “you want your taste affirmed by your peers and those you admire, but it’s just as vital that your redneck uncle thinks you’re an idiot to like that rap shit. It proves that you’ve distinguished yourself from him successfully, and you can bask in righteous satisfaction.”

THE CYCLE OF COOL

Cultural capital, like economic capital, is scarce. There is only so much time in a day to accumulate cultural capital, and most of us spend a great deal of our time pursuing it, recognizing its importance in our overall social standing. But cultural capital – what is “cool” – is always on the move. Capital attains its value by being scarce. Cultural capital – “what is cool” – maintains this scarcity by always being on the move. Being cool is a full-time job of carefully watching for trends and movement in the webs of significance we are collectively spinning.

Market researchers try to keep up with what is cool by tracking down trend-setting kids to interview them, study them, and follow them on social media. Once market researchers get in on a trend, they can create products to serve this new taste; but as soon as the mass consumer picks up on it, the trend-setter can no longer like it without being associated with the masses. Doug Rushkoff calls this the “cycle of cool.” Once that “cool” thing is embraced by the masses, it’s not cool anymore, because it’s no longer allowing people to feel that sense of distinction. Trend setters move on to the next cool thing, so that the mark of what is “cool” keeps moving.

Market researchers are also employed by media companies producing movies, TV shows, and music videos that need to reflect what is currently popular. In Merchants of Cool, a documentary about the dynamics of cool and culture in the early 2000s, Doug Rushkoff asks, “Is the media really reflecting the world of kids, or is it the other way around?” He is struck by a group of 13-year-olds who spontaneously broke out into sexually-laden dances for his camera crew the moment they started filming “as if to sell back to us, the media, what we had sold to them.” He called it “the feedback loop.” The media studies kids and produces an image of them to sell back to the kids. The kids consume those images and then aspire to be what they see. The media sees that and then crafts new images to sell to them “and so on … Is there any way to escape the feedback loop?” Rushkoff asks.

He found some kids in Detroit, fans of a rage rock band called Insane Clown Posse. They thought they had found a way to get out of the media machine by creating a sub-culture that was so offensive as to be indigestible by the media. With his cameras rolling, the kids yell obscenities into the camera and break out singing one of their favorite and least digestible Insane Clown Posse songs, “Who’s goin ti**y f*in?” one boy yells out and the crowd responds, “We’s goin ti**y f*in!” They call themselves Juggalos. They have their own slang and idioms, and they feel like they have found something that is exclusively theirs. “These are the extremes that teens are willing to go to ensure the authenticity of their own scene,” Rushkoff concludes. “It’s a double dog dare to the mainstream marketing machine,” Rushkoff notes, “Just try to market this.”

They did. Before Rushkoff could finish the documentary, the band had been signed by a major label, debuting at #20 on the pop charts.

WHY WE HATE

Growing up in a small town in Nebraska, I learned to hate Country music. One would think it would be the opposite. Nebraskans love Country music. But that was precisely the point. By the time I was a teenager, I had aspirations of escaping that little town. I wanted to go off to college, preferably out of state, and “make something of myself.” The most popular Country song of that time was by Garth Brooks singing, “I’ve Got Friends in Low Places.” I didn’t want friends in low places. I wanted friends (social capital) in other places, high places, so I tuned my taste (cultural capital) accordingly. I hated Garth Brooks. I hated Country music.

I loved Weezer. Weezer was a bunch of elite Ivy League school kids who sang lyrics like, “Beverly Hills! That’s where I want to be!” It was like a soundtrack for the life I wanted to live. “Where I come from isn’t all that great,” they sang, “my automobile is a piece of crap. My fashion sense is a little whack and my friends are just as screwy as me.” It seemed to capture everything I was, and everything I aspired to become.

My hatred for Country music bore deep into my consciousness as I associated it with a wide range of characteristics, values, beliefs, ideas, and ideals that I rejected and wanted to distinguish myself from. The hate stuck with me so that years later, I still could not stand to stay on a Country music station for long. I once heard a bit of a Kenny Chesney song about knocking a girl up and getting stuck in his small town. “So much for ditching this town and hanging out on the coast,” the song goes, “There goes my life.” Ha! I thought. I got out. Then I changed the channel.

Carl Wilson, a Canadian music critic, decided to do an experiment to explore these questions. He called it “an experiment in taste.” He would deliberately try to step outside of his own taste-bubble and try to enjoy something he truly hates. His plan was to immerse himself in music he hates to find out what he can learn about taste and how it works.

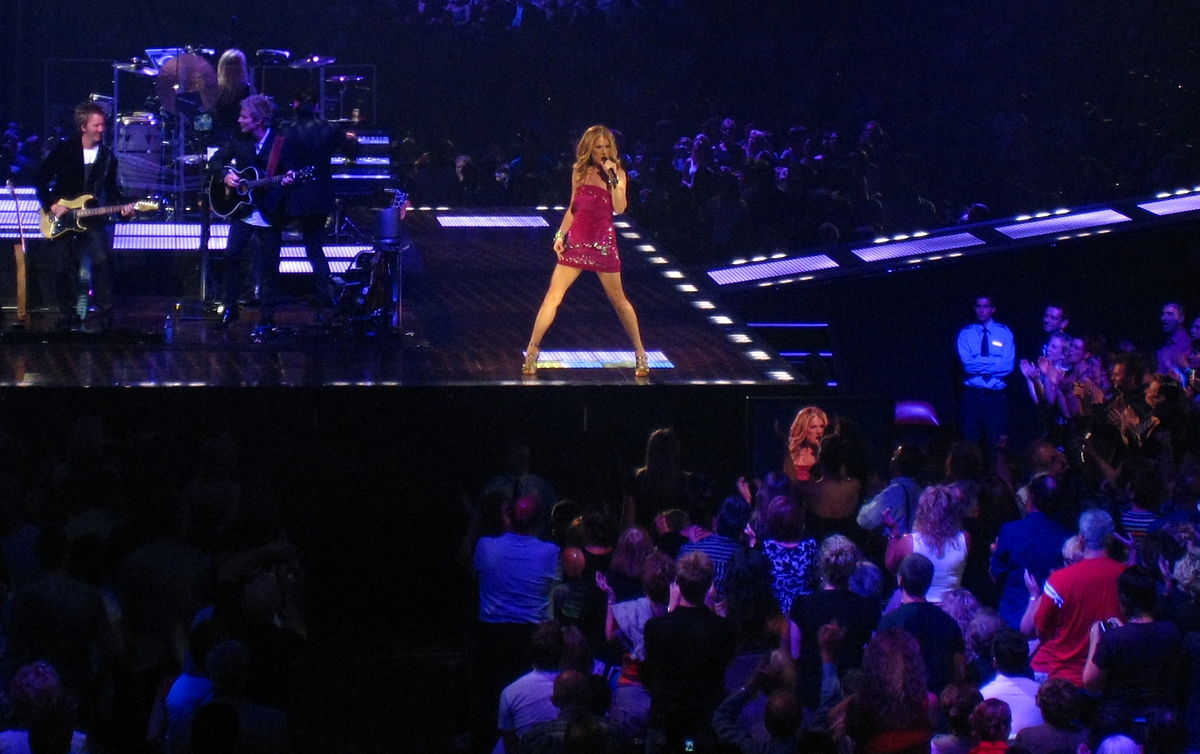

As he thought about what he hated most, one song immediately came to mind: Celine Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On.” The song rocketed to international popularity as the love song of the blockbuster movie Titanic in 1998. The song, and Celine Dion herself, have enjoyed global success that is almost unrivaled by any other song or celebrity. She sells out the largest venues all over the world. As the US entered Afghanistan in 2003, The Chicago Tribune noted that Celine was playing in market stalls everywhere, her albums being sold right beside Titanic-branded body sprays, mosquito repellant … even cucumbers and potatoes were labeled “Titanic” if they were especially large.

As a Canadian music critic with a vested interest in being cool among affluent urban intellectual hipsters, Wilson could not think of any song he hated more. In general, urban hipsters like Wilson love to bash Celine, and especially this song. Maxim put it at #3 in its ranking of “most annoying song ever” and called it “the second most tragic event to result from that fabled ocean liner.”

Wilson quotes Suck.com for calling Titanic a “14-hour-long piece of cinematic vaudeville” that teaches important lessons “like if you are incredibly good-looking, you’ll fall in love.”

Wilson’s hate for the song crystallized at the Oscars in 1998. Up against Celine’s love ballad was Elliot Smith’s “Miss Misery” a soul-filled indie love song about depression from Good Will Hunting that you would expect to hear from the corner of an authentic hip urban coffee shop. Smith was totally out of place at the Oscars. He didn’t even want to be there. It wasn’t his scene. He reluctantly agreed to sing when the producers threatened to bring in ’80s teen heart throb Richard Marx to sing it instead. As a compromise, he performed the song alone with nothing but his guitar. It wasn’t his kind of scene, but he would still do his kind of performance.

Then Celine Dion came “swooshing out in clouds of fake fog” with a “white-tailed orchestra arrayed to look like they were on the deck of the Titanic itself.” Elliot’s performance floated gently like a hand-carved fishing boat next to the Titanic performance of Celine. Madonna opened the envelope to announce the winner, laughed, and said with great sarcasm, “What a shocker … Celine Dion!” Carl Wilson was crushed, and his hate for Celine, and especially that song, solidified.

Wilson did not need to probe the depths of his consciousness to know that he hated that song, but he still did not know why he hated that song. Perhaps Bourdieu’s terminology could help, he mused. Turning to the notions of social and cultural capital, he started exploring Celine Dion’s fan base to see if he was using cultural capital to distinguish himself from some groups while affiliating himself with others.

He was not the first to wonder who likes Celine Dion. He quoted one paper (The Independent on Sunday) as offering the snarky musing that “wedged between vomit and indifference there must be a fan base: … grannies, tux-wearers, overweight children, mobile-phone salesmen, and shopping-centre devotees, presumably.” Looking at actual record sales, Wilson found that 45% were over 50, 68% female, and that they were 3.5 times more likely to be widowed. “It’s hard to imagine an audience that could confer less cool on a musician,” Wilson mused. It was no wonder he was pushing them away by pushing away from the music.

But he also noted that the record sales showed that they were mostly middle income with middle education, not unlike Wilson himself. Wilson aspires to be an intellectual and tries to write for an intellectual audience, but he has no clear intellectual credentials such as a Ph.D., and his income reflects this.

This brings up an important point about the things we hate: We often hate most that which is most like us. We have elevated anxieties about being associated with things that people might assume we would like, so we make extra efforts to distinguish ourselves from these elements. So Wilson pushes extra hard against these middle-income middle-educated Celine fans while attempting to pull himself toward the intellectual elite.

We often hate most that which is most like us.

This is not as simple as an intentional decision to dislike something just because it isn’t cool. It works at a much deeper level. The intellectual elite that Wilson aspires to be associated with talks and acts in certain ways. They have what Bourdieu calls a certain “habitus” – dispositions, habits, tastes, attitudes, and abilities. In particular, the intellectual elite tend to over-intellectualize and deny emotion. Nurturing this same habitus, Wilson hears a simple sappy love ballad on a blockbuster movie loved by the masses and immediately rejects it. It doesn’t feel intentional. He truly hates it, and that hatred is in part born out of this habitus.

HOW TO STOP HATING

Wilson pressed forward with his experiment. He met Celine’s fans, including a man named Sophoan, who was as different from Wilson as possible. He is sweet-natured and loves contemporary Christian music, as well as the winners of various international Idol competitions. “I’m on the phone to a parallel universe,” Wilson mused about their first phone conversation. But by the end of it, he genuinely likes Sophoan, and he is starting to question his own tastes. “I like him so much that for a long moment, his taste seems superior,” Wilson concludes. “What was the point again of all that nasty, life-negating crap I like?”

As Wilson explored his own consciousness a bit deeper, he started to realize just how emotionally stunted he had become. He had just been through a tough divorce. It wasn’t that he felt no emotion; it was that his constant tendency to over-intellectualize allowed him to never truly sit with an emotion and really feel it. Instead he would “mess with it and craft it … bargain with it until it becomes something else.”

Onward with the experiment. Wilson decided to listen to Celine Dion as often as possible. It took him months before he could play it at full volume, for fear of what his neighbors might think of him. He had developed, as he put it, a guilty pleasure. And the use of the word “pleasure” was intentional. He really was starting to enjoy Celine Dion.

“My Heart Will Go On” was more challenging, though. It wasn’t just that it had reached such widespread acceptance among the masses. It was that it had been overplayed too much to enjoy. “Through the billowing familiarity,” he writes, “I find the song near-impossible to see, much less cry about.”

That is, until it appeared in the TV show Gilmore Girls. After the divorce, Wilson found himself drawn to teenage drama shows. His own life was not unlike that of those teenage girls portrayed in the shows. Single and working as a music critic, he often goes out to shows and parties where he always struggles to fit in, find love, and feel cool among people who always seem to be a little cooler than him.

In the last season of Gilmore Girls, the shihtzu dog of the French concierge dies. The concierge is a huge Celine fan, and requests “My Heart Will Go On” for the funeral. The whole scene is one of gross and almost ridiculous sentimentality, but a deep truth is expressed through Lorelai, the lead character, as it dawns on her that her love for her own husband is not as deep or true as the love this concierge has for his dog. She knows it’s time to move on and ask for a divorce. Wilson starts to cry:

Something has shifted. I’m no longer watching a show about a teenage girl, whether mother or daughter. It’s become one about an adult, my age, admitting that to forge a decent happiness, you can’t keep trying to bend all the rules; you aren’t exempt from the laws of motion that make the world turn. And one of the minor ones is that people need sentimental songs to marry, mourn, and break up to, and this place they hold matters more than anything intrinsic to the songs themselves. In fact, when one of those weepy widescreen ballads lands just so, it can wise you up that you’re just one more dumb dog that has to do its best to make things right until one day, it dies. And that’s sad. Sad enough to make you cry. Even to cry along with Celine Dion.

I think back to my own experience with that Kenny Chesney song – the one about the guy getting stuck in the small town after getting a girl pregnant. After I became a father, I was driving home from a conference, back to be with my wife and infant son in Kansas. (We felt drawn back to small town life, and decided to settle close to home to start our family.) The singer describes his little girl smiling up at him as she stumbles up the stairs and “he smiles … There goes my life.” I, of course, am weeping uncontrollably at this point. I’m a different person. The song speaks to me, and completely wrecks me in a later verse as the chorus is invoked one last time in describing his little girl going off to college. There goes my life. There goes my future, my everything, I love you, Baby good-bye. There goes my life. (I can’t even type the words without crying.)

Like me, Wilson once hated that sappy music. But now, he says, “I don’t see the advantage in holding yourself above things; down on the surface is where the action is.”

But now, he says, “I don’t see the advantage in holding yourself above things; down on the surface is where the action is.”

By opening himself up to experiencing more, experiencing difference, and experiencing differently, Carl Wilson became more. He expanded his potential for authentic connection—not just to music, but also to other people. In his efforts to be cool, he spent a great deal of time trying to not be taken in by the latest mass craze, unaware that he was “also refusing an invitation out.” The experiment allowed him to move beyond this, open up to new experiences and more people. He started to see that the next phase of his life “might happen in a larger world, one beyond the horizon of my habits.”

LEARN MORE