On my first day of graduate school, I watched my new advisor, Roy Wagner, walk onto the stage in front of 200 undergraduates in his Anthropology of Science Fiction class and drop-kick the podium. The podium slid across the stage and crashed to the floor. But Roy was not yet satisfied. He picked up the podium and hurled it off the stage and launched into a tirade. He said he had heard a story that dozens of students had decided to take the class because they thought it would be an “easy A.” He wanted to assure them that this wasn’t the case, and invited anyone who was not fully committed to leave the room immediately. A couple dozen people walked out. Then he calmly picked up the podium, set it back up, warmly welcomed us to the class, and then proceeded to share with us “the secret” of anthropology: “Anthropology is storytelling.”

“Anthropology is storytelling.” – Roy Wagner

He proceeded to reveal the importance of anthropology in crafting the storyworlds of classic Science Fiction texts like Dune and The Left Hand of Darkness (written by Ursula Le Guin, the daughter of Alfred Kroeber, one of the most famous anthropologists of all time). But more importantly, he showed us the importance of storytelling in understanding and presenting the cultural worlds and life stories of others. As anthropologist Ed Bruner noted, “Our anthropological productions are our stories about their stories; we are interpreting the people as they are interpreting themselves.”

Of course, the real insight here is that we are all always “anthropologists,” in the sense that all of us are interpreting the stories of people around us, and the stories people tell about themselves are also simplified interpretations of a very complex history and web of deeply entangled experiences. But we are not just interpreting the stories of others, we are also constantly telling and retelling the story of our own selves. “Yumi stori nau!” is the most common greeting you will hear as you walk around Papua New Guinea.

The direct English transliteration: “You Me Story Now!” perfectly captures the spirit of the request. It is an expression of the joy felt when two people sit down and share stories together. In Nimakot, where there are no televisions or other media forms, storytelling is king, just as it has been for most humans throughout all time.

Among the Agta, hunter-gatherers in the Philippines, anthropologist Andrea Migliano found that when the Agta were asked to name the five people they would most like to live with in a band, the most sought-after companions were the great storytellers. Being a great storyteller was twice as important as being a great hunter. And this wasn’t just for the high-quality entertainment. Storytellers had a profound influence on the well-being of the group. Stories among the Agta often emphasize core cultural values such as egalitarianism and cooperation. So when Migliano’s team asked different Agta groups to play a game that involved sharing rice, the groups with the best storytellers also turned out to be the most generous and egalitarian in their sharing practices.

Being a great storyteller was twice as important as being a great hunter.

The storytellers were also highly valued for the cultural knowledge that they possess and pass on to others. Societies use stories to encode complex information and pass it on generation after generation.

As an example, consider an apparently bizarre and confusing story among the Andaman Islanders about a lizard that got stuck in a tree while trying to hunt pigs in the forest. The lizard receives help from a lanky cat-like creature called a civet, and they get married. What could this possibly mean? Why is a lanky cat marrying a pig-hunting lizard? Such stories can provide a treasure of material for symbolic interpretation, but the details of such stories also pass along key information across generations about how these animals behave and where they can be found. As anthropologist Scalise Sugiyama has pointed out, this is essential knowledge for locating and tracking game.

One especially provocative and interesting anthropological theory about storytelling comes from Polly Wiessner’s study of the Ju/’hoansi hunter-gatherers of southern Africa. While living with them, it was impossible not to notice the dramatic difference between night and day. The day was dominated by practical subsistence activities. But at night, there was little to be done except huddle by the fire.

The firelight creates a radically different context from the daytime. The cool of the evening relaxes people, and if the temperatures drop further they cuddle together. People of all ages, men and women, are gathered together. Imaginations are on high alert under the moon and stars, with every snap and distant bark, grumble or howl receiving their full attention. The light offers a small speck of human control in an otherwise vast unknown. They feel more drawn to one another, and the sense of a gap between the self and the other diminishes.

It is in this little world around the fire where the stories flow. During the day just 6% of all conversations involve storytelling. Practical matters rule the day. But at night, 85% of all conversation involves storytelling or myth-telling. As she notes, storytelling by firelight helps “keep cultural instructions alive, explicate relations between people, create imaginary communities beyond the village, and trace networks for great distances.”

Though more research still needs to be done, her preliminary work suggests that fire did much more for us than cook our food in the past. It gave us time to tell stories to each other about who we were, where we came from, and the vast networks of relations that connect us to others. The stories told at night were essential for keeping distant others in mind, facilitating vast networks of cooperation, and building bigger and stronger cultural institutions, especially religion and ritual. Fire sparked our imaginations and laid the foundation for the cultural explosion we have seen over the past 400,000 years.

Stories are Everywhere

Stories are everywhere, operating on us at every moment of our lives, but we rarely notice them. Stories provide pervasive implicit explanations for why things are the way they are. If we stop to think deeply, we are often able to identify several stories that tell us about how the world works, the story of our country, and even the story of ourselves. Such stories provide frameworks for how we assess and understand new information, provide a storehouse of values and virtues, and provide a guide for what we might, could, or should become. Most importantly, they do not just convey information, they convey meaning. They bring a sense of significance to our knowledge.

Stories are powerful because they mimic our experience of moving through the world – how we think, plan, act, and find meaning in our thoughts, plans, and actions.

We are in a constant process of creating stories. When we wake up, we construct a narrative for our day. If we get sick, we construct a narrative for how it happened and what we might be able to do about it. Through a wider lens, we might look at the story of our lives and construct a narrative for how we became who we are today, and where we are going. Through an even broader lens, we construct stories about our families, communities, our country, and our world.

Cultures provide master narratives or scripts that tell us how our lives should go. A common one for many in the West is go to school, graduate, get a job, get married, have kids, and then send them to college and hope they can repeat the story. But what happens when our lives go off track from this story? What happens when this story just doesn’t work for us? We find a new story, or we feel a little lost until we find one. We can’t help but seek meaning and coherence for our lives.

Alan Watts challenges the traditional narrative that “life is a journey”

What is the story of the world? Most people have a story, often unconscious, that organizes their understanding of the world. It frames their understanding of events, gives those events meaning, and provides a framework for what to expect in the future.

Jonathan Haidt proposes that most Westerners have one of two dominant stories of the world that are in constant conflict. One is a story that frames Capitalism in a negative light. It goes like this:

“Once upon a time, work was real and authentic. Farmers raised crops and craftsmen made goods. People traded those goods locally, and that trade strengthened local communities. But then, Capitalism was invented, and darkness spread across the land. The capitalists developed ingenious techniques for squeezing wealth out of workers, and then sucking up all of society’s resources for themselves. The capitalist class uses its wealth to buy political influence, and now the 1% is above the law. The rest of us are its pawns, forever. The end.”

In the other story, capitalism is viewed positively, as the key innovation that drives progress and lifts us out of poverty and human suffering. It goes like this:

“Once upon a time, and for thousands of years, almost everyone was poor, and many were slaves or serfs. Then one day, some good institutions were invented in England and Holland. These democratic institutions put checks on the exploitative power of the elites, which in turn allowed for the creation of economic institutions that rewarded hard work, risk-taking, and innovation. Free Market Capitalism was born. It spread rapidly across Europe and to some of the British colonies. In just a few centuries, poverty disappeared in these fortunate countries, and people got rights and dignity, safety and longevity. Free market capitalism is our savior, and Marxism is the devil. In the last 30 years, dozens of countries have seen the light, cast aside the devil, and embraced our savior. If we can spread the gospel to all countries, then we will vanquish poverty and enter a golden age. The end.”

You probably recognize both of these stories. They operate just beneath the surface of news articles, academic disciplines, and political movements. If we pause, think deeply, and take the time to research, we would probably all recognize that both stories offer some insights and truth, but both are incomplete and inaccurate in some respects.

Haidt proposes that we co-create a third story that recognizes the truths of both stories while setting the stage for a future that is better for everybody. His proposal is a reminder that once we recognize the power of stories in our lives, we also gain the power to recreate those stories, and thereby recreate our understanding of ourselves and our world.

The Wisdom of Stories

During the Great Depression, Joseph Campbell spent five years in a small shack in the woods of New York reading texts and stories from religious traditions all over the world. As he did so, he started to see common underlying patterns to many of the stories, and a common body of wisdom. One pattern he found was that of the hero’s journey. All over the world, he found stories of heroes who are called to adventure, step over a threshold to adventure, face a series of trials to achieve their ultimate boon, and then return to the ordinary world to help others.

He mapped out the hero’s journey in a book appropriately titled The Hero with a Thousand Faces in 1949. The book would ultimately transform the way many people think about religion, and have a strong influence on popular culture, providing a framework that can be found in popular movies like Star Wars, The Matrix, Harry Potter, and The Lion King. The book was listed by Time magazine as one of the 100 best and most influential books of the 20th century.

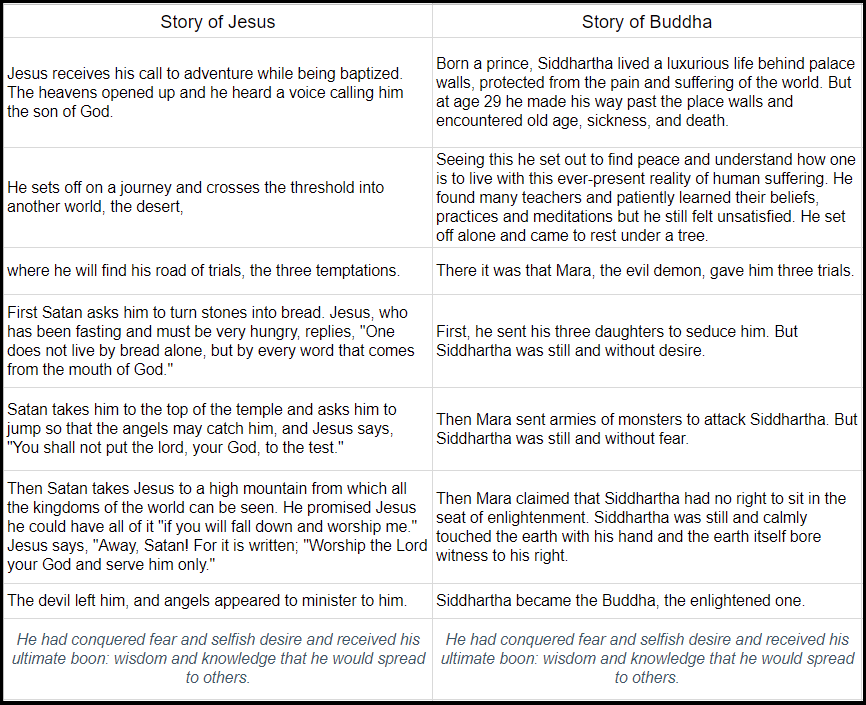

In an interview with Bill Moyers, Campbell refers listeners to the similarities in the heroic journeys of Jesus and Buddha as examples:

Both stories tell the tale of a hero who is unmoved by the selfish and socially destructive values of wealth, pleasure, and power to serve a higher purpose. Campbell was struck by ubiquitous themes he found across cultures in which people overcome basic human fears and selfish desires to become cultural heroes. In his book, he identified 17 themes that are common throughout hero stories around the world. They’re not all always present, but they are common. Seven of them are especially prominent and essential:

1. The Call to Adventure. The hero often lives a quintessentially mundane life, but longs for something more. Something happens that calls the hero forth into the adventure. The hero often hesitates but eventually accepts the call.

2. The Mentor. There is usually someone who helps the hero as he crosses the threshold into the land of adventure.

3. The Trials. The hero must face many tests and trials, each one offers a lesson and helps the hero overcome fear.

4. “The Dragon.” The hero’s biggest fear is often represented by a dragon or some kind of ultimate threat.

5. The Temptations. There are usually some temptations trying to pull the hero away from the path. These test the hero’s resolve and ability to quell their selfish desires.

6. The Ultimate Temptation: The ultimate temptation is usually the demand of social life, a “duty” we feel to be and act in a certain way that is not in alignment with who we really are.

7. Ultimate Boon. If the hero can move past fear and desire, he is granted a revelation and transforms into a new being that can complete the adventure.

That the same basic structure can be found all over the world in both story and ritual illuminates profound universals of the human condition. Specifically, all humans are born unfinished and in a state of dependency, and must make a series of major changes in identity and role throughout life. Hero stories highlight the key dilemmas we all must face.

But as Campbell studied the stories and traditions of the world, he became more and more concerned that modern society had lost its connection to the key wisdom and guidance that hero stories could provide. He worried that literal readings of the heroic stories in the Bible were not appealing to many people, because the core stories are based in a society of the Middle East 2,000 years ago when slavery was commonplace and women were not equals. Back then it was common to assume, as described in Genesis, that the world is relatively young, perhaps just a few thousand years old, and is shaped like a flat disc with a dome above it – the firmament of heaven – that holds the stars.

Such stories are hard to square with our current knowledge that the earth is over 4 billion years old and sits on the outer edge of a vast galaxy which is itself just a small piece of a larger universe that is about 14 billion years old.

As a result, Campbell lamented, both Christians and atheists do not receive the potential wisdom of religious stories because they are overly focused on whether or not the stories are true rather than trying to learn something from them.

Rebirth of the Hero

Campbell called on artists to develop new stories that could speak to the challenges of our times and serve the four functions of religion outlined earlier – stories that could teach us how to live a good life in today’s world (the pedagogical function), stories that could help us get along and feel connected to one another (the sociological function), stories that could give us a better picture and understanding of how things work today (the cosmological function), and stories that could allow us to feel hopeful and stand in awe of the universe (the mystical function).

George Lucas was one of the first to hear the call.

Lucas came across Campbell’s work while he was working on Star Wars. “It was a great gift,” Lucas said, “a very important moment. It’s possible that if I had not come across that I would still be writing Star Wars today.” Thanks to Campbell’s work, the stories of Jesus, Buddha, and other religious hero stories from all over the world came to influence characters like Luke Skywalker. George Lucas would refer to Campbell as “my Yoda,” and the influence of the great teacher is evident in the work.

Star Wars was just the first of many Hollywood movies that would use the hero cycle as a formula. In the mid-1980s Christopher Vogler, then a story consultant for Disney, wrote up a seven-page memo summarizing Campbell’s work. “Copies of the memo were like little robots, moving out from the studio and into the jetsream of Hollywood thinking,” Vogler notes. “Fax machines had just been invented … copies of The Memo [were] flying all over town.”

Movies have become the new modern myths, taking the elements of hero stories in the world’s wisdom traditions and placing them in modern day situations that allow us to think through and contemplate contemporary problems and challenges. In this way, elements of the great stories of Jesus and Buddha find their way into our consciousness in new ways.

Movies like The Matrix provide a new story that allows us to reflect on our troubled love-hate codependency-burdened relationship to technology. The hero, Neo, starts off as Mr. Anderson, a very ordinary name for a very ordinary guy working in a completely nondescript and mundane cubicle farm. His call to adventure comes from his soon-to-be mentor, Morpheus, who offers him the red pill. Mr. Anderson suddenly “wakes up,” literally and figuratively, and recognizes that he has been living in a dream world, feeding machines with his life energy. Morpheus trains him and prepares him for battle. Morpheus reveals the prophecy to Neo, who, Morpheus calls “The One” – the savior who is to free people from the Matrix and save humankind. (The name “Neo” is “One” with the O moved to the end of the word.) In this way, Neo’s story is very much like the story of Jesus. At the end of the movie, he dies and is resurrected, just like Jesus; but here the story takes a turn toward the East, as upon re-awakening Neo is enlightened and sees through the illusion of the Matrix, just as Hindus or Buddhist attempt to see through the illusion of Maya.

The religious themes continue in the second movie, as Neo meets “the architect” who created the Matrix. The architect looks like a bearded white man, invoking common images of God in the West. But invoking Eastern traditions, the architect informs Neo that he is the sixth incarnation of “The One” and is nothing more than a necessary and planned anomaly designed to reboot the system and keep it under control. Neo is trapped in Samsara, the ongoing cycles of death, rebirth, and reincarnation.

In order to break the cycle, Neo ultimately has to give up everything and give entirely of himself – the ultimate symbol of having transcended desire. In a finale that seems to tie multiple religious traditions together, Neo lies down in front of Deus Ex Machina (God of the Machines) with his arms spread like Jesus on the cross, ready to sacrifice himself and die for all our sins. But this is not just a Christian ending. Invoking Eastern traditions, he ends the war by merging the many dualities that were causing so much suffering in the world. Man and machine are united as he is plugged into the machines’ mainframe. And even good and evil are united as he allows the evil Smith to enter into him and become him. In merging the dualities, all becomes one, and the light of enlightenment shines out through the Matrix, destroying everything, and a new world is born.

The Matrix is an especially explicit example of bringing the themes of religious stories into the modern myths of movies, but even seemingly mundane movies build from the hero cycle and bring the wisdom of the ages to bare on contemporary problems. The Secret Life of Walter Mitty explores how to find meaning in the mundane world of corporate cubicles, and how to thrive in a cold and crass corporate system that doesn’t seem to care about you. The Hunger Games explores how to fight back against a seemingly immense and unstoppable system of structural power where the core exploits the periphery, and how to live an authentic life in a Reality TV world that favors superficiality over the complexities of real feelings and real life. And Rango, which appears to be a children’s movie about a pet lizard who suddenly finds himself alone in the desert, is a deep exploration of how to find one’s true self.

All these stories provide models for how we might make sense of our own lives, and as we will see in the concluding section to this lesson, incorporating what we learn from fictional heroes can have very real effects on our health and well-being.

Making Meaning

We all have a story in mind for how our life should go, and when it doesn’t go that way, we have to scramble to pick up the pieces and find meaning. Gay Becker, Arthur Kleinman, and other anthropologists have explored how people reconstruct life narratives after a major disruption like an illness or major cultural crisis. This need for our lives to “make sense” is a fundamental trait of being human, and so we find ourselves constantly re-authoring our biographies in an attempt to give our lives meaning and direction.

Psychologist Dan McAdams has studied thousands of life stories and finds recurring themes and genres. Some people have a master story of upward mobility in which they are progressively getting better day by day. Others have a theme of “commitment” in which they feel called to do something and give themselves over to a cause to serve others. Some have sad tales of “contamination” as their best intentions and life prospects are constantly spoiled by outside influences, while others are stories of triumph and redemption in the face of adversity.

These studies have shown that “making sense” is not just important for the mind; “making sense” and crafting a positive life story have real health benefits. When Jamie Pennebaker looked at severe trauma and its effects on long-term health, he found that people who talked to friends, family, or a support group afterward did not face severe long-term health effects. He suspected that this was because they were able to make sense of the trauma and incorporate it into a positive life story. In a follow up study, he asked one group to journal about the most traumatic experience of their lives for fifteen minutes per day for four days. In the control group, he asked them to write about another topic. A year later, he looked at medical records and found that those who had written about their trauma were less likely to get sick.

This was a phenomenal result, so Pennebaker looked deeper into what people had written during that time. There he found that the people who received the greatest health benefit were those who had made significant progress in making sense of their past trauma and experiences. They had re-written the story of their lives in ways that accommodated their past trauma.

McAdams and his colleagues have found that when people face the troubles and trials of their lives and take the time to make sense of them, they construct more complex, enduring, and productive life stories. As a result, they are also more productive and generative throughout their lives, and have a stronger sense of well-being.

But how do we craft positive stories in the face of adversity and find meaning and sense in tragedy and trauma? There are no secret formulas. People often find their stories of redemption by listening with compassion to the stories of others. In other words, they simply adopt the core anthropological tools of communication, empathy, and thoughtfulness to open themselves up to the stories of others. This is what makes our own life stories, as well as the legends and hero stories written into our religions and scripted on to the big screen so powerful and important. It’s why we sat up by flickering fires for hour after hour for hundreds of thousands of years, and why we still find wisdom in the flickering images of movies and television shows.

LEARN MORE

“Embers of Society: Firelight talk among the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen” by Paul Wiessner. PNAS 111(39):14027-14035.

The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human by Jonathan Gottschall

The Power of Myth, by Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers. Book and Video.

The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom, by Jonathan Haidt

What Really Matters: Living a Moral Life amidst Uncertainty and Danger, by Arthur Kleinman