The Most Basic Story Structure

The 3 Act Structure

- Beginning

- Middle

- End

Seems almost too simple, but it makes a huge difference to

- actually create a beginning that sets the scene and invites the viewer in

- give your viewer a reason to keep watching through the middle

- and actually conclude the piece in a way that makes it feel finished, like something has been said and no more is needed

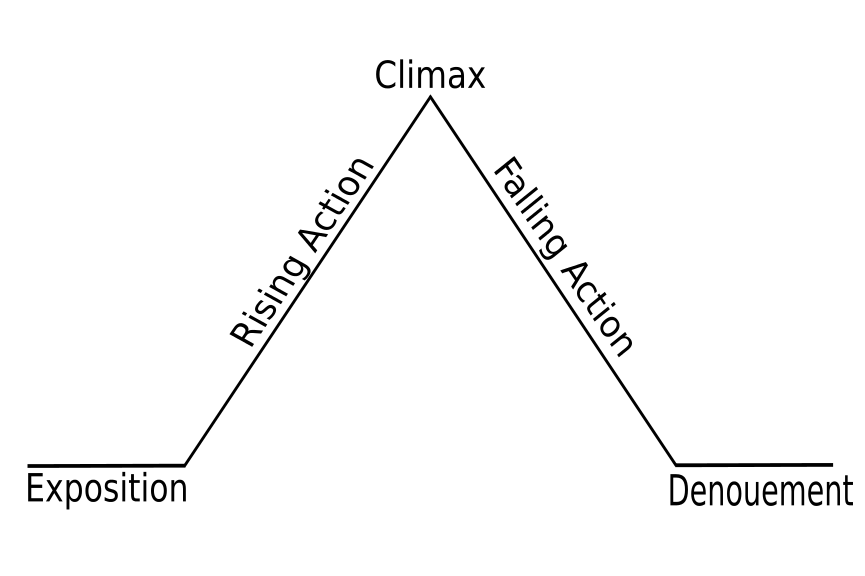

Slightly more complex: 5 Parts of Dramatic Arc

- Exposition – Setting, character development, dramatic tension, conflict

- Rising Action – Key conflicts and tensions develop over time

- Turning Point – Key climax that resolves conflicts/tensions above

- Falling Action – Showing the outcome of the resolution & reflecting on it

- Denouement – Allows the audience to absorb what has happened and connect

This is sometimes called Freytag’s Pyramid:

Check out the setup, rising action, climax, and conclusion in this remarkable video short by Brandon Li. It’s Freytag’s Pyramid without a single word of dialogue:

The Hero Structure

- We often start with a pile of ideas from our ideafest. Next, we have to grow the ideas.

- Let the story reveal itself. Get your story to talk by asking it questions.

- Each idea of Campbell’s Monomyth gives you a question to ask your story

Act One:

- The Normal World

- The Inciting Incident

- The Call to Adventure

- Hero refuses the adventure

- Hero accepts the adventure

Act Two:

- The Road of Trials (trailer footage)

- Often a false victory here that adds drama, depth, and mystery

- Learning about true love (Meeting the Goddess)

- Learning about duty / how to deal with societal/parental pressures (Father Atonement)

- Resisting desires and temptations to get off the path (Woman as Temptress)

- all of the above are ripe for B-Stories

- Achieve new knowledge in 1 or all of 3 areas above (Apotheosis)

- Ultimate Boon – Quest apparently achieved

Act Three:

- Refusal of the return. Hero may have apparently won, but the return is difficult or undesired.

- Magic flight. Adventurous return to the normal world.

- Rescue from Without. A key helper may arrive to save the day (often the climax/resolution to the B-Story)

- Crossing the Return threshold. The challenge of integrating the new knowledge into the old normal

- Master of Two Worlds. Hero successfully integrates knowledge, creating a new normal.

What about non-fiction documentaries?

Sometimes the hero is your audience and you have to take them on the hero’s journey. Here is how the 17 stages might translate. This is just a creative exercise. You can translate them however you like. The key is to let them be good questions to ask your story.

[table id=3 /]

How to structure a video essay?

- Never tell a story with “and then …”

- Every beat should be “therefore” or “but”

- In non-fiction you might be connecting thoughts rather than scenes

- “meanwhile back at the ranch” b-story line, let each one peak and tack back and forth

- consider multiple lines

- They are not essays, they are films. Pacing matters.

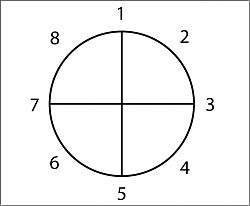

The Storyclock Method

- Set the clock to length of your piece

- Break it into quadrants

- Put in the events you know must be in there

- Fill in the gaps

- Look for symmetries and connections

Getting Deep with Dan Harmon

Video Summary

- 0:00 – The importance of stories

- 0:33 – All stories are the same

- 0:56 – Joseph Campbell’s Monomyth

- 2:00 – Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

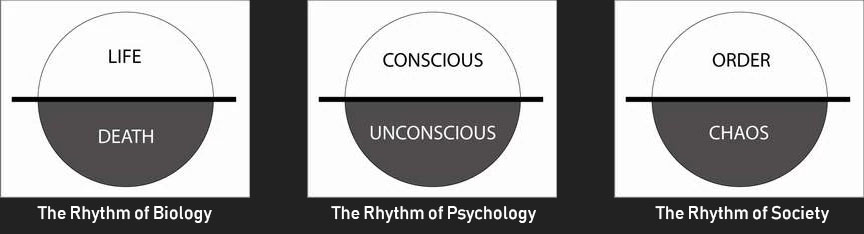

- 2:55 – Harmon’s 3 dualities: life/death, consciousness/unconsciousness, order/chaos

- 3:30 – 3 dualities are biological, psychological, and sociological (Body, Spirit, Society)

- 4:48 – Four quadrants and 4 transition points

- 5:10 – You, Need, Go, Search, Find, Take, Return, Change

- 5:33 – Transitions = key dramas

- 6:10 – Dualities play out across the circle

- 6:30 – Analysis of Star Wars

- 13:20 – It can apply to any piece of the story. Circles for each character, for the theme, tone, etc.

Dan Harmon can’t resist elevating the story.

Always thinking “How do I make this more compelling?”

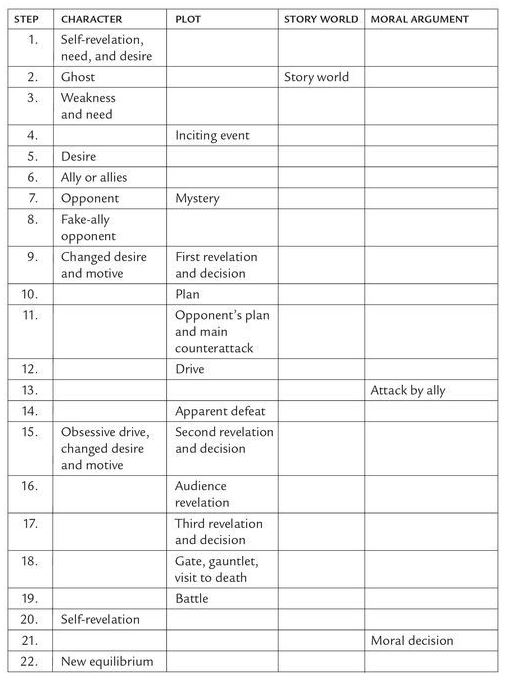

Builds from Truby’s dynamic of weakness and need

John Truby sees a story as weaving together 4 strands:

- Character development

- Plot

- Storyworld (setting & context)

- Moral Argument (theme, point, lesson)

His 22-Part structure weaves together like this:

Dan Harmon’s “Super Basic Shit”

- A character is in a zone of comfort,

- But they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation,

- Adapt to it,

- Get what they wanted,

- Pay a heavy price for it,

- Then return to their familiar situation,

- Having changed.

“Super Basic Shit” applied to every sitcom ever:

Dan Harmon’s Pure Boring Theory

Now you understand that all life, including the human mind and the communities we create, marches to the same, very specific beat. If your story also marches to this beat- whether your story is the great American novel or a fart joke- it will resonate. It will send your audience’s ego on a brief trip to the unconscious and back. Your audience has an instinctive taste for that, and they’re going to say “yum.”

The next step is to get these rhythms to lay over the 8-point circle, allowing the critical tensions and transformations between life/death, consciousness/unconsciousness, and order/chaos to line up with the 1-5 line and the 3-7 line. If you do it right, you should see some oppositions and tensions on each end of those lines.

That’s the big overview, but if you want to craft a masterpiece, be sure to check out the “Juicy Details” or if you are crafting a 5-minute video (more the scope of this class) check out his bit on Five Minute Pilots.

Experimental Storytelling

It can be useful at this stage of the project to think way outside the box and look at other forms of storytelling. For example, here is a story performed live by Siobhan O’Loughlin who will come to your house to perform her one-woman play: Broken Bone Bathtub.

Or consider shadow-dancing

Or the growing trend of immersive theatre:

Do all great ethnographic videos have a story?

Yes. All *great* ones do … I think. (I’m willing to be proven wrong.) Many ethnographic videos do not. But that is why they are not resonating. They don’t grab the core human rhythms that Harmon identifies, create gaps between what is and could be, and draw us into an arc that builds in intensity.

Check out this video by Brandon Li. Is there a story driving it or is it just a bunch of pretty pictures set to music?

Now check out this one, made one year later:

0:00 – Setting the scene – the Ordinary World – What we expect of Vegas

0:20 – Transition into the other side. We moved from conscious to unconscious

Visually we moved from chaos to order, but in reality we are in the chaos of the unconscious, exploring humankind’s deepest needs

0:35 – Broken V_GAS sign highlights the theme

1:00 – The gambling, performances, and sexuality are being framed within deeper needs

2:00 “Someone like you” is a coda that shows people getting together

2:40 “I hope it’s going to make you notice” – he lets the music pull him through

3:10 – Climax – the lonely woman who seemed to have no one has someone … everybody has somebody … fireworks, dancing

3:43 – Return to ordinary world, but everything is now different.

The viewer has changed. We are the hero. We will never see Vegas the same again.

So how do we find stories in real life?

Follow an event:

Use the dramatic arc to frame daily life, waking up … action … riding off into the sunset:

Use a local poem or song:

The hero story … Normal World, Initiation, Trials, Death, Rebirth (Literally in this case)

Invent a fictional story to guide you through the city:

Next Challenge: A Very Short Story

Your challenge will be to write a single paragraph that establishes your topic, story, plot, and theme. The paragraph should be a short story in and of itself and serve as a setting off point for your journey toward a more complex and complete story later in the course.

Complete “very short stories” will:

- be actual stories with “therefore” and “but” statements, and no “and thens”

- take inspiration from one or more of the structures above,

- have a clear beginning, rising action, climax, resolution, and denouement

- have a clear theme (point, message)

Note that future challenges will build on this. Up next, you will record yourself reading your story and lay down found footage and audio tracks to build a compelling “trailer” of sorts.